A few years ago T. V. Venkatasubramanian, Robert Butler and myself made a translation of Sorupa Saram and had it published in The Mountain Path (2004, pp. 75-103). It turned out to be highly popular. The issue sold out almost immediately, the only time this has ever happened. Once the last copy had been sold, xeroxed copies of the Word document I submitted to the magazine were given to those who could not obtain copies of the magazine itself.

The man who composed this work, Sorupananda, had a disciple called Tattuvaraya who eventually became just as famous as his Guru. In this four-part post Venkatasubramanian, Robert and myself have collected all the known facts of Tattuvaraya’s life and translated some of his voluminous writings. The four sections cover the following topics:

Part one: The life of Tattuvaraya and the relationship he had with his Guru Sorupananda.

Part two: a full translation of Sorupa Saram. Though this has appeared both in The Mountain Path and on my site, there may be new readers here who have not seen this wonderful text before.

Part three: extracts from Amrita Saram, one of Tattuvaraya's works on Vedanta.

Part four: translations of songs from Paduturai by Tattuvaraya. The selections include advice to sadhakas, expressions of gratitude towards his Guru, and verses in which he declares his own experience of the Self.

Part two: a full translation of Sorupa Saram. Though this has appeared both in The Mountain Path and on my site, there may be new readers here who have not seen this wonderful text before.

Part three: extracts from Amrita Saram, one of Tattuvaraya's works on Vedanta.

Part four: translations of songs from Paduturai by Tattuvaraya. The selections include advice to sadhakas, expressions of gratitude towards his Guru, and verses in which he declares his own experience of the Self.

Sorupananda and Tattuvaraya appear in several Ramanasramam publications, with their names being spelled in a variety of ways: ‘Tatvaroyar’,‘Tatva Rayar’ and ‘Swarupananda’ can all be found. I have standardised the spellings as Sorupananda and Tattuvaraya in all four parts of this post.

* * *

Tattuvaraya was a Tamil saint and poet whom scholars believe flourished in the late 15th century. He was a prolific author who wrote thousands of verses on a wide variety of spiritual topics. Bhagavan noted in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, talk no. 648, that he was ‘the first to pour forth advaita philosophy in Tamil’. Prior to his arrival on the Tamil literary scene, advaita texts in Tamil seem to have been translations of, or expositions on, texts composed in Sanskrit.

One of Tattuvaraya’s compositions was mentioned several times by Bhagavan. This is how he narrated the story in Day by Day with Bhagavan, 21st November 1945:

Tattuvaraya composed a bharani [a kind of poetical composition in Tamil that features military heroes who win great battles] in honour of his Guru Sorupananda and convened an assembly of learned pandits to hear the work and assess its value. The pandits raised the objection that a bharani was only composed in honour of great heroes capable of killing a thousand elephants, and that it was not in order to compose such a work in honour of an ascetic. Thereupon the author said, ‘Let us all go to my Guru and we shall have this matter settled there’. They went to the Guru and, after all had taken their seats, the author told his Guru the purpose of their coming there. The Guru sat silent and all the others also remained in mauna. The whole day passed, night came, and some more days and nights, and yet all sat there silently, no thought at all occurring to any of them and nobody thinking or asking why they had come there. After three or four days like this, the Guru moved his mind a bit and thereupon the assembly regained their thought activity. They then declared, ‘Conquering a thousand elephants is nothing beside this Guru’s power to conquer the rutting elephants of all our egos put together. So certainly he deserves the bharani in his honour!’

There is a very similar retelling of the bharani incident in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, talk no. 262.

Sorupananda, his Guru, was also his maternal uncle. Early on in their life they had made an arrangement whereby they would both seek Gurus in different places. Tattuvaraya travelled to the north of India from Virai, their home town, Sorupananda to the south. The agreement further stipulated that whichever of the two attained the grace of the Guru first would become the Guru of the other. Sorupananda became the disciple of Sivaprakasa Swami and realised the Self with him. Then, to fulfil the agreement with his nephew, he became his Guru.

In Letters from Sri Ramanasramam (letter dated 8th April 1948) Bhagavan gives a brief summary of how Sorupananda became Tattuvaraya’s Guru:

This afternoon when I [Suri Nagamma] went to Bhagavan, I found someone singing a song, ‘Gurupada Mahima’ [Greatness of the Guru's Feet].

After the singing was over, looking at me, Bhagavan said: ‘These songs have been written by Tattuvaraya Swami. You have heard of the sacredness of the feet of the Guru, haven’t you?’

‘Yes. I have heard the songs. As the meaning of the songs is profound I thought some great personage must have written them,’ I said.

‘Yes. There is a story behind it,’ remarked Bhagavan. When I enquired what it was, Bhagavan leisurely related to us the story as follows:

‘Both Tattuvaraya and Sorupananda decided to go in search of a Sadguru in two different directions. Before they started they came to an understanding. Whoever finds a Sadguru first should show him to the other. However much Tattuvaraya searched he could not find a Sadguru. Sorupananda, who was the uncle of Tattuvaraya, was naturally an older man. He went about for some time, got tired, and rested in a place.

Feeling he could no longer go about in search, he prayed to the Lord, ‘O Iswara! I can no longer move about. So you yourself should send me a Sadguru.’

Having placed the burden on the Lord, he sat down in silence. By God’s grace, a Sadguru came there by himself, and gave him tattva upadesa (instruction for Self-realisation).

This story was originally published in Letters from and Recollections of Sri Ramanasramam as letter number five. The letters from this volume have now been added to the enlarged and consolidated edition of Letters from Sri Ramanasramam.

Though Tattuvaraya was a prolific author, only one work has ever been attributed to Sorupananda: Sorupa Saram, a 102-verse poem about the nature of the experience of the Self. This work was so highly valued by Bhagavan, he included it on a list of six titles that he recommended to Annamalai Swami. Since the other five were Kaivalya Navaneetam, Ribhu Gita, Ashtavakra Gita, Ellam Ondre, and Yoga Vasishta, Sorupa Saram is in distinguished company.

Tattuvaraya realised the Self quickly and effortlessly in the presence of Sorupananda. The opening lines of Paduturai, one of his major works, reveal just how speedily the event took place:

The feet [of Sorupananda], they are the ones that, through grace, and assuming a divine form, arose and came into this fertile world to enlighten me in the time it takes for a black gram seed to roll over. (Tiruvadi Malai, lines 1-3)

Black gram is the variety of dhal that is one of the two principal ingredients of iddlies and dosa. It is 2-3 mm across and slightly asymmetrical, rather than spherical. This property led Tattuvaraya to write, in another verse, that Sorupananda granted him liberation in the time it took for ‘a [black] gram seed to wobble and turn over onto its side’. (Nanmanimalai verse 10)

Tattuvaraya attributed this near-instantaneous enlightenment wholly to the power and grace of his Guru, rather than to any intrinsic merit, maturity or worthiness:

It is possible to stop the wind. It is possible to flex stone. But what can be done with our furious mind? How marvellous is our Guru, he who granted that this mind should be totally transformed into the Self! My tongue, repeat this without ever forgetting.

When my Lord, who took me over by bestowing his lotus feet, glances with his look of grace, the darkness in the heart vanishes. All the things become completely clear and transform into Sivam. All the sastras are seen to point towards reality.

Most glorious Lord, if you hadn’t looked upon me with your eye of divine grace, how could I, your devotee, and the mind that enquired, experience the light that shines as the flourishing world, as many, as jnana, and as one?

To destroy me, you gave me one look in which there was no looking. You uprooted the ignorance of ‘I’ and ‘mine’. You brought to an end all the future births of this cruel one. O Lord, am I fit for the grace that you bestowed on me? (Venba Antadi, vv. 12, 14, 60, 69)

Sorupananda’s mind-silencing ability is quite evident both from the story of the bharani that Bhagavan told on several occasions and from the verses in which Tattuvaraya spoke of this transmission from his own direct experience. Tattuvaraya even stated in some places, somewhat hyperbolically, that Sorupananda, unlike the gods, bestowed instant liberation on everyone who came into his presence:

[In order to convince the devas] Brahma, [lacking the power] to make them experience directly the state of being, held the red-hot iron in his hand and declared, ‘This is the ultimate reality declared by the Vedas. There is nothing else other than this. I swear to it.’ Siva as Dakshinamurti declared, ‘In all the worlds, only the four are fit; they alone are mature for tattva jnana.’ Lord [Krishna], holding the discus, had to repeat eighteen times to ignorant Arjuna, who was seated on the wheeled chariot. But here in this world [my Guru] Sorupananda bestows jnana on all as palpably as the gem on one’s palm. (Tiruvadi Malai lines 117-126)

‘Eighteen times’ refers to the chapters of the Bhagavad Gita.

The Brahma Gita is the source of the story mentioned at the beginning of the verse. This text was translated from Sanskrit into Tamil by Tattuvaraya himself. His version of the relevant verses, taken from chapter five, is as follows:

96 The four-faced One [Brahma], he who creates all the worlds and is their Lord, said, ‘You [gods] who love me well, listen! Since it is I who declare to you that this is the meaning of the arcane Vedas, this is the reality beyond compare. If you are in any doubt, I will have the iron heated till it is red hot and hold it in my golden hands to prove myself free of any falsehood.’

97 He who sits upon the lotus blossom [Brahma] said, ‘[Gods, you who are] loving devotees [of Lord Siva], listen! The meaning of the Vedas, as I have explained it, is just so. There is nothing further. In order that you should be convinced of this in your minds, I have sworn a threefold oath, holding onto the feet of Lord [Siva].

Holding a red-hot iron in one’s hand was ancient trial-by-ordeal way of affirming the truth. If the flesh of the hand did not burn, then the statement uttered was deemed to be true.

Tattuvaraya made the claim in the Tiruvadi Malai lines that his Guru was more powerful and more capable of granting enlightenment than the trimurti of Brahma, Vishnu in the form of Krishna, and Siva. Elaborating on this theme, Tattuvaraya stated that Siva, appearing as Dakshinamurti, only managed to enlighten the four sages (Sanaka, Sanandana, Sanatkumara and Sanatsujata); Brahma had to resort to holding a red-hot iron and taking an oath to persuade his deva followers that his teachings were true; whereas Krishna, despite giving out the extensive teachings that are recorded in the Bhagavad Gita, wasn’t able to enlighten even Arjuna. Though this is a somewhat harsh assessment, the inability of Krishna to enlighten Arjuna through his Gita teachings was mentioned by Bhagavan himself:

Likewise, Arjuna, though he told Sri Krishna in the Gita ‘Delusion is destroyed and knowledge is imbibed,’ confesses later that he has forgotten the Lord’s teaching and requests Him to repeat it. Sri Krishna’s reiteration in reply is the Uttara Gita. (Sri Ramana Reminiscences, p. 52)

While all this might sound slightly blasphemous, it is a long and well-established position in Saivism that, when it comes to enlightening devotees, the human Guru is more effective and has more power than the gods themselves.

Though Tattuvaraya knew that it was the immense power of his Guru that had granted him liberation, he was at a loss to understand why that power had ultimately singled him out as a worthy recipient of its liberating grace. In one of his long verses he ruminated on the mysterious nature of prarabdha – why events had unfolded the way they did in various narratives of the gods – before chronicling the circumstances of his own liberation in a stirring peroration:

When [even] the gods despair; when those who investigate the paths of every religion become confused and grow weary; when even they fail to reach the goal, they who perform great and arduous tapas, immersing themselves in water in winter, standing in the midst of fire in summer, and foregoing food, so that they experience the height of suffering, I do not know what it was [that bestowed jnana upon me]. Was it through the very greatness of the noble-minded one [Sorupananda]? Or through the nature of his compassion? Or was it the effect of his own [absolute] freedom [to choose me]? I was the lowest of the low, knowing nothing other than the objects of sense. I was lost, limited to this foul body of eight hands span, filled with putrid flesh. But he bade me ‘Come, come,’ granting me his grace by looking upon me with his lotus eyes. When he spoke that single word, placing his noble hands upon my head and crowning it with his immaculate noble feet, my eye of jnana opened. [Prior to this] I was without the eye [of jnana], suffering through births and deaths for countless ages. [But] when he commanded me ‘See!’, then, for me, there was no fate; there was no karma; there was no fiery-eyed death. All the world of differentiated forms became simply a manifestation of Sorupananda. (Nanmanimalai, v. 37, lines 28-50)

The lines that immediately precede this extract discuss destiny, karma and death, and mention a claim that it is impossible to destroy them. Tattuvaraya then disagrees, citing his Guru Sorupananda’s statement: ‘We have routed good and evil deeds in this world; we have destroyed the power of destiny; we have escaped the jaws of Yama [death].’ (Nanmanimalai v. 37, lines 24-26)

In the portion of the verse cited here Tattuvaraya emphatically backs up this claim by saying that when his own eye of jnana was opened through the look and touch of his Guru, ‘for me, there was no fate; there was no karma; there was no fiery-eyed death. All the world of differentiated forms became simply a manifestation of Sorupananda.’

There are other verses which reaffirm Tattuvaraya’s statement that after he had been liberated by Sorupananda he knew nothing other than the swarupa which had taken the form of Sorupananda to enlighten him:

All that appears is only the swarupa of Sorupan[anda]. Where are the firm earth, water and fire? Where is air? Where is the ether? Where is the mind, which is delusion? Where indeed is the great maya? Where is ‘I’?

[In greatness] there is no one equal to Sorupan. Of this there is no doubt. Similarly, there is no one equal to me [in smallness]. I did not know the difference between the two of us when, in the past, I took the form of the fleshy body nor later when he had transformed me into himself by placing his honey-like lotus feet [on my head]. Now I am incapable of knowing anything. (Nanmanimalai, vv. 38, 39)

Let some say that the Supreme is Siva. Let some say that the Supreme is Brahma or Vishnu. Let some say that Sakti and Sivam are Supreme. Let some say that it is with form. Let some say that it is formless. But we have come to know that all forms are only our Guru. (Venba Antadi, v. 8)

Tattuvaraya wrote of the consequences of his realisation in a poem entitled ‘Pangikku Uraittal’ (Paduturai, v. 64), which can be translated as ‘The Lady Telling her Maid’. The second of the five verses, which speaks of the simple, ascetic life he subsequently led, was mentioned with approval by Bhagavan in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, talk no. 648:

1

Our reward was that every word we heard or said was nada [divine sound].

Our reward was to have ‘remaining still’ [summa iruttal] as our profession.

Our reward was to enter the company of virtuous devotees.

My dear companion, this is the life bestowed by our Guru.2

Our reward was to have the bare ground as our bed.

Our reward was to accept alms in the palms of our hands.

Our reward was to wear a loincloth as our clothing.

My dear companion, for us there is nothing lacking.

Bhagavan’s comment on this verse was:

I had no cloth spread on the floor in earlier days. I used to sit on the floor and lie on the ground. That is freedom. The sofa is a bondage. It is a gaol for me. I am not allowed to sit where and how I please. Is it not bondage? One must be free to do as one pleases, and should not be served by others.

‘No want’ is the greatest bliss. It can be realised only by experience. Even an emperor is no match for a man with no want. The emperor has got vassals under him. But the other man is not aware of anyone beside the Self. Which is better?

The poem continues:

3

Our reward was to be reviled by all.

Our reward was that fear of this world, and of the next, died away.

Our reward was to be crowned by the lotus feet of the Virtuous One [the Guru].

My dear companion, this is the life bestowed by our Guru.4

Our reward was the pre-eminent wealth that is freedom from desire.

Our reward was that the disease called ‘desire’ was torn out by the roots. Our reward was the love in which we melted, crying, ‘Lord!’

Ah, my dear companion, tell me, what tapas did I perform for this?

There is an indirect reference in the first line to Tirukkural 363: ‘There is no pre-eminent wealth in this world like freedom from desire. Even in the next, there is nothing to compare to it.’

The final verse says:

5

Our reward was to wear the garment that never wears out.

Our reward was to possess as ‘I’ the one who is present everywhere.

Our reward was to have [our] false devotion become the true.

My dear companion, this is the life bestowed by our benevolent Guru.

‘The garment that never wears out’ is chid-akasa, the space of consciousness.

After his realisation Tattuvaraya subsequently spent much of his time absorbed in the Self. Sorupananda knew that his disciple had a great talent for composing Tamil verses and wanted him to utilise it. However, to bring him out of his inner absorption and to set him on the literary path, he knew he had to coax him out of his near-perpetual samadhi state.

This is how the story unfolds in the traditional version of Tattuvaraya’s life. The indented biographical details in the account that follows are all taken from an introduction to a 1953 edition of Tattuvaraya’s Paduturai, published by Chidambaram Ko. Chita. Madalayam. They appear on pages 8-16.

Sorupananda thought, ‘This Tattuvaraya is highly accomplished in composing verses in Tamil. Through him, we should get some sastras composed for the benefit of the world.’

He indicated his will through hints for a long time, but as Tattuvaraya was in nishta [Self-absorption] all the time, he could not act on the suggestions.

Sorupananda eventually decided to accomplish his objective by following a different course of action.

Pretending that he wanted to have an oil bath on a new-moon day, he turned to his attendant and asked, ‘Bring oil’.

Tattuvaraya, who was standing nearby, knew that it was amavasya [new-moon day]. He began to speak by saying ‘Am…’ and then stopped.

It is prohibited to have an oil bath on amavasya. This breach with custom was sufficient to bring Tattuvaraya out of his Self-absorption. He spontaneously uttered ‘Am…’, presumably as a prelude to saying that it was amavasya, but then he stopped because he realised that it would be improper of him to criticise any action his Guru chose to perform. This gave Sorupananda the opportunity he was looking for:

As soon as he heard Tattuvaraya speak, Sorupananda pretended to be angry with him.

He said, ‘Can there be any prohibitions for me, I who am abiding beyond time, having transcended all the sankalpas that take the form of dos and don’ts? Do not stand before me! Leave my presence!’

Tattuvaraya thought to himself, ‘Because of my misdeed of prescribing a prohibition for my Guru, who shines as the undivided fullness of being-consciousness-bliss, it is no longer proper for me to remain in this body. There can be no atonement other than drowning myself in the sea.’

With these thoughts in his mind, he walked backwards while still facing his Guru, shedding torrents of tears at the thought of having to leave his presence.

Other versions of this story make it clear that Tattuvaraya walked backwards away from his Guru’s presence because he felt that it was improper to turn his back on his Guru. Though it is not clear in this particular retelling, he apparently walked backwards until he reached the shore of the sea where he intended to drown himself. The narrative continues:

Through the compassion he felt for other beings and through the power of the Self-experience that possessed him, he began to compose verses as he was walking [backwards towards the ocean]. These were the eighteen works he composed in praise of both his Guru and his Paramaguru [Sivaprakasa Swami]. These were noted down by some of Sorupananda’s other disciples.

As he continued to sing these eighteen works, the disciples who were following him took down what he said, [conveyed the verses to] Sorupananda, and read them in his presence.

Sorupananda pretended not to be interested: ‘Just as a woman with hair combs and ties it, this one with a mouth is composing and sending these verses.’

Another version of Tattuvaraya’s life states that Sorupananda had sent disciples to write down the verses that Tattuvaraya was composing, so his lack of interest should not be taken to be genuine. It was all part of a ruse to get his disciple to begin his literary career.

Meanwhile, Tattuvaraya was pining and lamenting: ‘Alas, I have become unfit to have the darshan of my Guru. Henceforth, in which birth will I have his darshan?’

Like a child prevented from seeing its mother, he was weeping so much, his whole face became swollen. At this point he was singing ‘Tiruvadi Malai’ from Paduturai. He was close to the edge of the sea and was about to die.

When the disciples went to Sorupananda and updated him about these events, he [relented and] said, ‘Ask the ‘Guruvukku Veengi’ [the one whose obsessive desire for his Guru is making him ill] to come here’.

When Tattuvaraya heard about this, he was completely freed from his bodily suffering, and he also regained the power to walk [forwards].

The Pulavar Puranam, an anthology of the biographies of Tamil poet-saints, reports in verse thirteen of its Tattuvaraya chapter that he was already neck-deep in the sea when Sorupananda summoned him to return. The story continues:

He [Tattuvaraya] told the disciples [who had arrived with the message], ‘Sorupananda, the repository of grace and compassion, has ordered even me, a great offender, to return’.Iru is the imperative of a verb that means both ‘Be’ and ‘Stay’. In choosing this word Sorupananda was ordering him both to remain physically with him and also to continue to abide in the state of being.

Experiencing supreme bliss, he sang some more portions of Paduturai, and then returned to the presence of the Guru. He stood there, shedding tears, in ecstasy, singing the praises of his Guru.

Sorupananda merely said, ‘Iru’.

Tattuvaraya lived happily there, serving his Guru.

Sorupananda went through the works that Tattuvaraya had composed and was delighted with their depth of meaning and the grandeur of their vocabulary. However, he made no sign of the joy he felt.

Then he thought to himself, ‘These sastras will be useful only for the learned and not for others’.

He told Tattuvaraya, ‘Son, you have sung all these sastras for your own benefit, but not for the benefit of the people of the world’.

The conversation was interrupted by the arrival of the cooks who informed Sorupananda, ‘Swami, you should come to have your food’.

When Sorupananda went for his meal, Tattuvaraya, who was left alone, pondered over the words of his Guru. Concurring with his remarks, he composed Sasivanna Bodham before Sorupananda had returned from eating his meal. He placed it at the feet of his Guru [when Sorupananda reappeared] and prostrated. Sorupananda was delighted at the simplicity of its style and the speed with which Tattuvaraya composed poetry.

The next incident is the story of the bharani that Bhagavan narrated and referred to. There are several sources of Tattuvaraya’s life, and the details vary from text to text. The version that appears in this narrative is slightly different from the one Bhagavan told, and it also has a few extra details:

Tattuvaraya composed some Vedanta sastras, but was mostly in samadhi. Around that time some Virasaivas, who were on a pilgrimage, along with some pandits, came before Tattuvaraya, who was sitting in the presence of Sorupananda.

[They read the bharani and complained:] ‘A bharani is [only] sung about great heroes who have killed a thousand male elephants on the battlefield. How is it that you have composed this [kind of poem] on your Guru who has not heard of or known heroic valour even in his dreams?’

To this Tattuvaraya replied, ‘As our Guru kills the ego-elephants of disciples, I sang in this way’.

They responded, ‘The ego-elephant that you mention is not visible to the eye, so it is not proper [to compose in this way]. However, even to kill one ego-elephant would take many, many days. How did he manage to kill the egos of 1,000 disciples simultaneously?’

Tattuvaraya, thinking that they should be shown through a demonstration, resumed his samadhi state, without replying to them.

Under the power and influence of Sorupananda all the pandits who came remained in paripurnam [had the full experience of the Self] for three days, without knowing either night or day. On the fourth day Tattuvaraya opened his eyes. All the pandits arose and prostrated to both Tattuvaraya and Sorupananda.

They said, ‘It was because of our ignorance that we objected. The power of your [Sorupananda’s] presence is such that even if 10,000 disciples happen to come, it [the presence] has the ability to bring them all to maturity simultaneously.’

Then they composed their own verses in praise of the bharani and departed.

It is not unreasonable or fanciful to compare the relationship of Tattuvaraya and Sorupananda with the one that existed between Muruganar and Bhagavan. Tattuvaraya and Muruganar came to their Gurus (who both liked to teach through silence) and realised the Self soon afterwards. They both subsequently composed thousands of verses that either praised their respective Gurus, or recorded some aspect of their teachings. Tattuvaraya’s poems in praise of his Guru (and Sivaprakasa Swami, his Guru’s Guru) include Venba Antadi (100 verses), Kalitturai Antadi (100 verses), Irattaimanimalai (20 verses), Nanmanimalai (40 verses), Jnana Vinodan Kalambagam (101 verses), Kali Madal (232 verses), Ula (393 verses), and many, many more. Then there was the bharani that Bhagavan mentioned: a 493-verse poem (Ajnavatai Bharani) on the annihilation of ignorance by the ‘hero’ Sorupananda. Mokavatai Bharani was another 850-verse bharani on the killing of delusion that includes in its text 110 songs in which a goddess instructs her followers in Vedanta. These 110 songs are often published independently as a Tamil primer on Vedanta under the title Sasivanna Bodham. This is the work that Tattuvaraya composed while Sorupananda was having his meal.

There are, in addition, two long anthologies of Tamil poetry that contain more of Tattuvaraya’s verses: Peruntirattu (The Great Anthology), and Kuruntirattu (The Short Anthology). Though these anthologies mostly contain works by other authors, Tattuvaraya contributed some verses to both collections, and he is also acknowledged as the compiler of both books.

Muruganar, at Bhagavan’s behest, composed Sri Ramana Sannidhi Murai, modelling it on Manikkavachagar’s Tiruvachakam. In another interesting parallel Tattuvaraya composed Paduturai, a 1,140-verse collection of verses that are derived from contemporary folk songs. This work is also loosely based on Tiruvachakam. The ‘Lady Telling her Maid’ poem that appeared earlier in this article comes from this collection of verses.

Though Tattuvaraya clearly played a Muruganar-like role in the life of Sorupananda, it is interesting and a little intriguing to note that Satyamangalam Venkataramayyar, the author of Sri Ramana Stuti Panchakam, addresses Bhagavan himself as ‘Tattuvaraya’ in the second line of verse nine of ‘Kalaippattu’. This poem is chanted every Saturday evening in Bhagavan’s samadhi hall.

In addition to the original Tamil compositions and the anthologies he compiled, Tattuvaraya also translated Brahma Gita and Iswara Gita from Sanskrit into Tamil.

Despite this prolific literary output, it is fair to assume that Tattuvaraya regarded as his greatest accomplishment the state that was bestowed on him by his Guru Sorupananda:

What if the world praises me henceforth or reviles me? What if Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, remains close to me or separate from me? What if the body assuredly exists without ever decaying or perishes? Will there be any gain or loss to me on account of them, I who have worn perfectly on my head the twin feet of immaculate Sorupananda? (Jnana Vinodan Kalambagam v. 99)

The passing of both Sorupananda and Tattuvaraya is described in the traditional story of their lives:

Sorupananda started to wander aimlessly, leaving Tattuvaraya behind. Tattuvaraya followed him. When Sorupananda reached the sea shore, the waters separated to let him enter. However, when Tattuvaraya tried to do the same [and follow him], the sea did not part.

Tattuvaraya stood on the shore, crying loudly, like a calf separated from its mother. He searched for his Guru in all directions. Finally, Sorupananda appeared to give him [a final] darshan before shining as akanda paripurna satchitananda [the undivided transcendent fullness, being-consciousness-bliss].

In the context of what follows, this is the author’s way of saying that Sorupananda took mahasamadhi.

After performing his Guru’s samadhi rites, Tattuvaraya was constantly thinking of Sorupananda. Either through the supreme love he felt for him, or through his inability to bear the separation, or because of the understanding that there was nothing for him to do apart from his Guru, he immediately attained mahasamadhi.

Tattuvaraya’s samadhi shrine is located at Irumbudur, which lies between Vriddhachalam and Chidambaram.

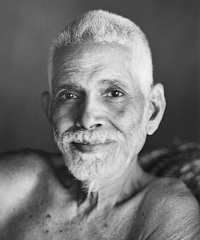

Tattuvaraya's samadhi shrine. The president of Sri Ramanasramam, Sri V. S. Ramanan, can be seen on the right.

15 comments:

Dear David,

I am very happy to see the first two parts of the four part series on Tattuvaraya's works. About the particular issue of 2004, MP, when I picked up the old issues of MP in the bookdepot of the Asramam, in 2008, I could collect all but this issue of Moutain Path, in which your translation of Sorupa Saram. By giving this English rendering, I am personally benefited to a large extent.

One more thing about this Sorupa Saram. In the 18 book, five volume [or even more] of Kovilur Math publications [where four volumes have already appeared], I am not able to find out Sorupa Saram. They have given four books of Tattuvarayar viz., Sasivanna Bodham, Ajnavada Bharani, Iswara Gita and Brahma Gita, but not Sorupa Saram. That way, I am benefited personally at least to have the English rendering by you [three]. Of these, Iswara Gita has been recently reprinted by Asramam.

In case a xerox copy of Tamizh version of Sorupa Saram could be made available to the blog members [on individual requests], I shall be able to send you the cost plus courier charges, by money order.

I know you don't like a DD or cheque.

Thanks for every thing.

Subramanian

So far as I am aware, there is no Tamil work still in print that contains the original text of Sorupa Saram. When we did the translation in 2004, we worked from a xeroxed copy.

Since this was a work recommended by Bhagavan, and since it is no longer available in Tamil, I have decided to publish a small booklet that will have the Tamil text on one side of the page and our English translation on the other. I will post a notification here when it is available.

Dear David,

Thank you very much for your reply

and also your proposal to bring out the booklet on Sorupa Saram and its English rendering.

wowowwwoowwww!!! :)

What a treat David! How could anyone thank you enough for these priceless posts!!

[....The lines that immediately precede this extract discuss destiny, karma and death, and mention a claim that it is impossible to destroy them. Tattuvaraya then disagrees, citing his Guru Sorupananda’s statement: ‘We have routed good and evil deeds in this world; we have destroyed the power of destiny; we have escaped the jaws of Yama [death].’ (Nanmanimalai v. 37, lines 24-26) ]

The above lines remind me of UG's 'Afterwash-Beforewash' simile.Watch the following video especially from time line 3:25

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrfQwJcHj8U

The gist seems to be:We cannot link a Jnani's path(cause) to his realisation(effect) and think we can achieve it by doing the same.Having said that an ajnani has to choose a path as he has no other choice.Each to his own path.Once he realises he changes his line and says there is no path, no realisation, no ajnani and all that.This is what UG seems to be conveying and Tattuvarayar seems to have had the same classic problem of conveying the Truth and path to the Truth.

-Z

Dear Anon.,

It is worth comparing Nanmani Maalai

verse that you have quoted with Sri

Bhagavan's two verses in ULLadu Narpadu.

Verse 19: The debate, "Does free will prevail or fate?" is only for those who do not know the root of both. Those who have known the Self, the common source of free will and of destiny, have passed beyond them both and will not return to them.

Verse 38: If we are the doers of deeds, we should reap the fruits they yield. But when we question, 'Who am I?', the doer of this deed?' and realize the Self, the sense of agency is lost and the three karmas slip away. And Eternal is this Liberation.

Sorupa Saram for german readers:

Das advaitische Tor, page 106

Dear David,

On my second reading today, the phrase Guruvukku Veengi, made me

thoughtful. An earnest disciple or a devotee waits for Guru and during the interval, he keeps on weeping, with the result his cheeks gets swollen etc., Saint

Manikkavachagar also says, that he was like a small bush or plant that was caught between two fighting mad elephants, when he could not leave the world nor could Siva take him without delay. Like this wonderful, similes are given in Tamizh poems.

In the olden days, the usual mums where the cheeks get swollen due to some infection is called Ponnukku Veengi, swelling for the gold[en ornaments]! the rural belief being that if that girl or boy is given a necklace or ear studs, she or he will be cured of these mums!

Again the usage Azhuguni Siddhar. This Siddhar was said to be always weeping for Siva darsanam, or Sivam {realization}. And then there was Paampaati Siddhar. He was not showing any sports with Paampu - snake. He was able to raise the kundalini, which is in the form of a coiled snake.

David,

Thanks a lot for this post!

One sentence of one of the poems says 'Our reward was to be reviled by all' I don't quite understand why they were reviled?

Thank you very much for this post.

I love reading scriptures which are relating with Bhagavan.They are inspiring.

But compared with Bhagavan's teaching,I feel scripures less practical and more complicated.

dear David Godman,

Excellent work.Tough task but still persistence guided you.can you inform me who did the website renovation work?They did the good job too.Much better than a year ago.

Om Mani Padme Hung!

The True Sound of Truth

A devoted meditator, after years concentrating on a particular mantra, had attained enough insight to begin teaching. The student's humility was far from perfect, but the teachers at the monastery were not worried.

A few years of successful teaching left the meditator with no thoughts about learning from anyone; but upon hearing about a famous hermit living nearby, the opportunity was too exciting to be passed up.

The hermit lived alone on an island at the middle of a lake, so the meditator hired a man with a boat to row across to the island. The meditator was very respectful of the old hermit. As they shared some tea made with herbs the meditator asked him about his spiritual practice. The old man said he had no spiritual practice, except for a mantra which he repeated all the time to himself. The meditator was pleased: the hermit was using the same mantra he used himself -- but when the hermit spoke the mantra aloud, the meditator was horrified!

"What's wrong?" asked the hermit.

"I don't know what to say. I'm afraid you've wasted your whole life! You are pronouncing the mantra incorrectly!"

"Oh, Dear! That is terrible. How should I say it?"

The meditator gave the correct pronunciation, and the old hermit was very grateful, asking to be left alone so he could get started right away. On the way back across the lake the meditator, now confirmed as an accomplished teacher, was pondering the sad fate of the hermit.

"It's so fortunate that I came along. At least he will have a little time to practice correctly before he dies." Just then, the meditator noticed that the boatman was looking quite shocked, and turned to see the hermit standing respectfully on the water, next to the boat.

"Excuse me, please. I hate to bother you, but I've forgotten the correct pronunciation again. Would you please repeat it for me?"

"You obviously don't need it," stammered the meditator; but the old man persisted in his polite request until the meditator relented and told him again the way he thought the mantra should be pronounced.

The old hermit was saying the mantra very carefully, slowly, over and over, as he walked across the surface of the water back to the island.

glow

Dear Sri Godman,

A tamil text and commentary of the Sourupasaram in Tamil is available for download from Digital Library of India. This Tamil commentary is by Easoor Sachithananthaswamy published in 1900. Last four verses are missing. The Ramanashramam can publish this work. No copyright is available now. PDF file is about 5.6 MB. If you send your email address I will be very happy to e mail this to you.

With respect and regards,

K.Mohan,

Thiruvananthapuram

9446101991

Ananthapureesan

We consulted a later edition of this text, one that was published in 1950.

A bilingual edition (Tamil and English)of the whole text of Sorupa Saram can now be purchased from the Sri Ramanasramnam Book Depot. Four independent versions of the original Tamil text were consulted before we finalised the version that appears in this book.

Dear Sri. David Godman,

Thank you for the kind information. I shall get the book from Sri Ramanashramam during my next visit.

ARUNACHALA.

MOHAN.K

Post a Comment